News

News

3 On Your Side Investigates: State of Corruption

JACKSON, MS (WLBT) – At least once a month, the state auditor says a public official in the Magnolia State gets caught embezzling money — with demands equaling more than $2.5 million since last July.

Depending on where you live, that could be your tax dollars.

Five years ago, researchers ranked Mississippi the most corrupt state in the country based on federal convictions of public officials.

However, the study failed to answer one question: why does that kind of corruption happen so often here?

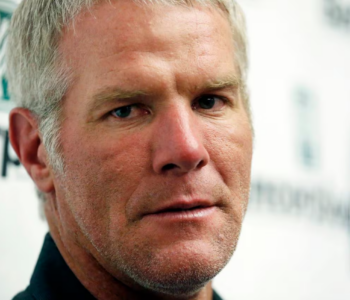

“I don’t think that Mississippians are any more or less corrupt than any other group of people. I do think that we have a structure of government with a lot of small layers of government that do lend themselves to corruption,” said State Auditor Shad White.

Few people know more about corruption than White.

After all, it’s his staff’s job to investigate dozens of cases a year.

Many of those involved embezzlement in the hundreds of thousands:

- $673,000: Investigators say during Thomas C. Tolliver’s time as the Wilkinson County Chancery Clerk, he exceeded his fee cap for the position and failed to reimburse the county for employee salary expenses. Tolliver died on Aug. 21, 2018, and the demand was issued against his estate.

- $302,973.19: Documents obtained by the auditor’s office indicate the former town clerk of Coldwater, George Nangah, made over $116,000 in unapproved purchases for items like gift cards and a GoPro camera. Nangah is also accused of issuing more than $46,000 in unapproved payments to himself and acquiring $53,000 in a kickback scheme. Nangah also faces a federal indictment on multiple counts of wire fraud.

- $279,764.16: Humphreys County Chancery Clerk Lawrence Browder is accused of fraudulently obtaining money from the county by forcing his staff to create false court records. Investigators say Browder pocketed money from the fees that came with those records, filing cases that did not exist. He’s also accused of exceeded his salary cap and paid himself more than $200,000 over the course of several years.

- $981,600.64: Former Coahoma Community College employees Gwendolyn Jefferson and Stacie Neal, according to the state auditor, conspired to embezzle money from their employer by creating false purchase documents and making personal purchases with credit cards and checks belonging to the community college. This case represents the largest individual demand for embezzlement by the Mississippi Office of the State Auditor in five years.

In fiscal year 2018 alone, the state auditor’s office demanded more than $3 million in taxpayer dollars in 45 of the state’s 82 counties.

Most of those are rural, according to data provided by the Office of Management and Budget.

“I think Mississippi is particularly vulnerable to embezzlement and fraud because of how small our entities of government are, how widespread they are. It’s easy to get out into rural Mississippi and folks can operate out there, and they think we’re not watching,” White said.

But they are, he insists.

White determines how likely an area will have fraud based on three factors: pressure, like financial pressure; opportunity, and rationalization.

“They’ll think, ‘well, I don’t get paid enough and it’s okay that I take a little bit extra off the top. I don’t want to take this money, I want to borrow it, and I’m gonna borrow a hundred dollars,’ and then a hundred dollars turns into a thousand, a thousand turns into ten thousand, and then there’s no way to pay it back,” White said.

The opportunity comes, White said, because the Magnolia State has a lot of small institutions that aren’t likely to have internal auditors or accountants who provide checks and balances.

That’s where it gets difficult for the Auditor’s Office.

Forensic accountant David Pray, who audits and investigates state agencies through PEER, said the sheer number of public agencies that fall within the auditor’s purview is staggering.

“The state auditor’s office has a tremendous responsibility because they’ve got all the counties to audit. There’s 82 of those, about 150 school districts have to be audited, municipalities, not to mention local entities, boards and commissions,” Pray said.

Some of these are so small, most may never have heard of them, like the Town Creek Master Water Management District Board of Commissioners in north Mississippi.

The auditor’s office said those commissioners steadily increased their own pay over nearly two decades, to the tune of $350,000.

Nobody knew it was happening until White’s team began investigating it.

That’s where public accountability comes in.

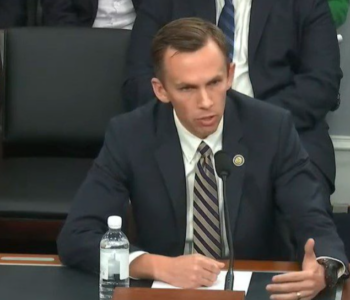

“The number one thing we can do is have an engaged citizenry and people go to these meetings. Watch your government at work. Ask questions. See what’s going on,” said Aaron Rice with the Mississippi Justice Institute. “Don’t be intimidated to show up at any government agency’s meeting. These are public meetings. They work for you.”

Rice said it’s our job to scrutinize our elected or appointed officials who spend our tax dollars.

“If you’ve seen something, even if it’s already taking place at a board meeting and you’re not sure that you know the state law was followed, you can call us, tell us what happened, and we’re happy to look into it,” Rice said.

White encourages people to look for warning signs, too.

“If you’ve got one person who’s in charge of taking the invoice, cutting the check, taking in money, making the deposit, writing down what happened in the accounting software, one person is doing all that, they have too much power, too much control. It doesn’t matter how much you trust them,” White said.

You can also request to see public records, too — budgets, emails, and invoices — to keep your own local government officials in check.

“The better informed taxpayers are about how their money is spent, the better we will all be.”

Auditor Shad White says the number one way they get information is from whistle blowers and tips.

Some states even give a financial incentive to those citizens concerned about corruption.

Called a false claims act, it allows residents to bring fraud cases against a public body on behalf of the state.

Whatever the state receives, that person gets a portion of it.

Thirty-one states have some form of that false claims act in place to help weed out corruption.

Mississippi, however, isn’t one of them.

If you see something you think should be investigated, you can also reach out to us by calling the 3 On Your Side Investigates Line. at 769-2300-TIP. You can also email us at Investigates@wlbt.com.