News

News

Money for Welfare Instead Funded Concerts, Lobbyists and Football…

ATLANTA (New York Times) — The state of Mississippi allowed tens of millions of dollars in federal anti-poverty funds to be used in ways that did little or nothing to help the poor, with two nonprofit groups instead using the money on lobbyists, football tickets, religious concerts and fitness programs for state lawmakers, according to a scathing audit released on Monday.

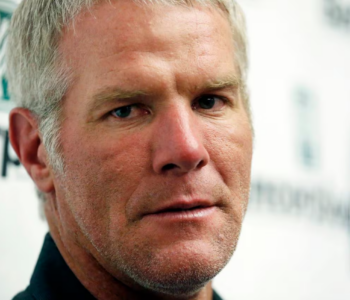

According to the report, released by the state auditor’s office, the money also enriched celebrities with Mississippi ties, among them Brett Favre, a former N.F.L. quarterback whose Favre Enterprises was paid $1.1 million by a nonprofit group that received the welfare funds. The payments were for speaking engagements that Mr. Favre did not attend, the auditors said.

Other large sums went to a family of pro wrestlers whose flamboyant patriarch, Ted DiBiase, earned national fame performing as the “Million Dollar Man.” In a news conference on Monday, Shad White, the state auditor, said it was possible that many recipients of the money did not know it had come from the federal welfare program.

Mr. Favre could not be reached for comment Monday. Mr. DiBiase declined to comment.

Mr. White called the findings “the most egregious misspending my staff have seen in their careers.” The audit found that more than $98 million from the federal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program, or TANF, was funneled to the two Mississippi-based nonprofit groups over three years. About $94 million of that was “questioned” by state auditors, meaning the money was in all likelihood misspent or the auditors could not verify that it had been spent legally, Mr. White said.

The breadth of the audit — which auditors said included funds that were “misspent, converted to personal use, spent on family members and friends of staffers and grantees or wasted” — raises broad questions about the efficacy of America’s social safety net.

In 1996, the TANF program converted the old federal welfare system, in which cash benefits to poor families were deemed an entitlement, to a system of block grants issued to the states. The new program created work rules and time limits on aid — and, notably, gave each state much more leeway on how to spend the money. Critics say that states do not have to clearly justify that they are spending the money on helping the poor.

“There’s this incredible amount of flexibility,” said LaDonna Pavetti, vice president for family income support policy at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. “It could allow for a lot of things to happen.”

Mississippi Republican lawmakers concerned about the misuse of federal funds have enacted safeguards to prevent fraud by potential welfare recipients. A ThinkProgress article found that in 2016, only 167 of the 11,700 Mississippi families who applied for a TANF payment were approved.

For those who support anti-poverty initiatives, the unfolding scandal has left a particularly bitter taste. “It’s just, ‘How can you?’” said Oleta Garrett Fitzgerald, southern regional director for the Children’s Defense Fund.

Monday’s audit comes after the arrest in February of John Davis, the former director of the Mississippi Department of Human Services, the agency that distributes the federal welfare block grants. Mr. Davis is accused of taking part in a multimillion-dollar embezzlement scheme.

Five other people were charged in the apparent scheme, including Nancy New, a politically connected figure who was the executive director of the Mississippi Community Education Center, one of the two nonprofit groups mentioned in the report. All have pleaded not guilty.

According to the auditor’s report, sub-grantees who received federal money through Mr. Davis’s group told auditors that Mr. Davis often signed off verbally on the projects they intended to fund, leaving holes in any paper trail. Mr. Davis’s nephew and brother-in-law received work contracts, either through his department, Ms. New’s group, or the other nonprofit group that received money, the Family Resource Center of North Mississippi, the audit states.

Mr. Davis, in a statement to a congressional committee last year, said that Mississippi welfare officials were using the program “to address the needs of those we serve. We see this as a way to eliminate one of the last barriers to finding true self-sufficiency for those who seek to not be dependent on needs-based programs.”

The report also shed light on payments made to entities connected to the wrestling family, and the mixture of self-help and evangelizing that the welfare money was supposedly funding. Mr. DiBiase is listed on federal tax forms as the principal officer of a religious nonprofit called Heart of David Ministries. The report shows the ministry received roughly $1.9 million over three years.

One of his sons, Ted DiBiase Jr., also a wrestler, is listed on state records as the registered agent and officer of a company called Priceless Ventures, which offered a self-help program, “The Law of 16.” The company received more than $2 million, auditors said.

A Law of 16 workbook submitted to Congress features inspirational quotes from Ted DiBiase Jr. and the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Auditors said that another son of the elder Mr. DiBiase, Brett DiBiase, also a wrestler, was paid with welfare funds to teach antidrug classes. But Mr. DiBiase, who was one of the six people indicted in February, never gave those classes, auditors said.

Ms. New, the head of the Mississippi Community Education Center, is a well-connected longtime educator who ran a private school in Jackson. Her work in the welfare field was feted by conservatives for helping poor people achieve self-sufficiency.

Mr. White’s office, in a statement, said the group was “particularly dependent” on TANF funding “and engaged in significant misspending.” From 2016 to 2019, the statement said, the group was given more than $60 million in welfare money, and raised less than $1.6 million from other sources.

Among the questionable spending by the nonprofit, the statement said, was the purchase of three trucks costing more than $50,000 each, which Mr. White said were used by Ms. New and two of her sons. Her lawyer could not be reached for comment.

The broader scandal is one of numerous major problems the state is facing, including the coronavirus pandemic and a prison system in crisis.

Danny Blanton, a spokesman for the human services department, said on Monday that steps were being taken to clean it up, including a planned forensic audit. Mr. White said that a state criminal investigation into the misuse of funds continues, in coordination with federal investigators.

Richard Fausset is a correspondent based in Atlanta. He mainly writes about the American South, focusing on politics, culture, race, poverty and criminal justice. He previously worked at the Los Angeles Times, including as a foreign correspondent in Mexico City.