News

News

3 On Your Side Investigates: Cooking the Books

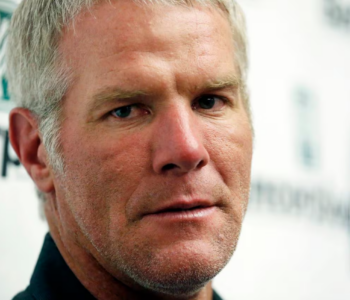

JACKSON, Miss. (WLBT) – Despite investigating public officials in twenty-two counties and demanding $5 million of your tax dollars be paid back in 2019, State Auditor Shad White believes his investigators are winning the fight against corruption in the Magnolia State.

At the same time, he encourages the public to keep an eye on who you elect and who they appoint.

“They could be the nicest person ever. They could treat you the right way when you’re face to face, but behind your back, they are stealing your money,” White said.

White’s purpose for rooting out these financial improprieties is two-fold.

First, he wants to get as much of that taxpayer money back as possible. In 2019, White says his office managed to obtain and return $2 million back to taxpayers.

Second, he hopes by publicizing these cases of embezzlement and misappropriation, it will eventually generate a culture change in Mississippi.

“Folks tend to convince themselves that there’s no victim when they steal this money. People see a river of public money flowing underneath their nose,” White said. “They tend to think of it as just money that is in the office that belongs to government, and so it becomes much easier to rationalize taking that money.”

Sometimes, those in power think they deserve that extra cash, too.

While Rankin County Sheriff Bryan Bailey said his department doesn’t deal with public corruption cases — instead deferring to Auditor White or the county’s district attorney — he sees similarities in the embezzlement cases they do pursue that involve small businesses.

“I’ve seen small doctor’s offices, small businesses with a bookkeeper. At the end of the day, it’s been hundreds of thousands of dollars that have been taken from this person that gave them their career, gave them their livelihood, that they’ve robbed this money from,” Bailey said. “I think they justify in their own mind over time, ‘I deserve this. I’m entitled to this.’”

If they’re not caught right away, Bailey said that justification only gets worse.

“On most of them, it’s like, ‘I would borrow twenty dollars. I’m gonna pay it back when we get paid. I’m running a little bit short.’ Then the twenty turns into a hundred, the hundred turns into a thousand,” Bailey said.

Take the most recent State Auditor’s case involving Paula Hunt, a former bookkeeper with the Warren County Tax Collector’s Office.

She pleaded guilty in November to embezzling money by stealing cash from payments received by the office and concealing it through money transfers between office bank accounts.

Those ten months of deception ended up costing taxpayers there more than $140,000.

In rare cases, those accused have claimed they didn’t know the behavior was illegal. White said ignorance of the law is no excuse.

“We do 75 training sessions around the state every single year to go out and tell people who work in government the rules for properly handling public money,” White said.

Even then, his trainers and investigators can’t be everywhere.

The auditor’s office versus potential tax dollar thieves almost seems like David fighting Goliath.

That’s where public accountability comes in.

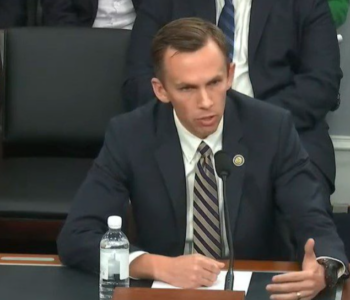

“The most important things we can do is go to meetings, request records, and stay on top of our government, and make sure they’re conducting our business, not self-interests or special interests, or self-dealing,” said Aaron Rice, who heads the Mississippi Justice Institute. “And that can happen in closed spaces with no eyes watching.”

When you go, make sure you scrutinize what those public officials are talking about:

- Request to see the public body’s minutes, its budget, and even its employee salaries to make sure they’re spending money in the right place.

- If it’s a public utility, ask for copies of their service line maps and those service histories to see how often they’re being maintained or repaired.

- Don’t think an alderman or city council member is doing what they should be? Request the person’s phone records, text messages and travel records.

- If you’re concerned that county supervisors are turning down industry opportunities, request their public calendars and follow up with companies that didn’t build there.

- Pay attention to how much money nonprofit organizations connected with a city or county generate, including “main street” associations, economic development authorities and chambers of commerce.

- Look at how much that organization’s executive director makes. In many cases, they make more than any other elected official in the county, aside from a school superintendent.

Speaking of schools, ask for your school district or university’s line-item budget.

Mississippi law requires many city and county agencies to provide public documents like that for free if you choose to inspect them in person.

Should you choose to request public records in writing, a public body must respond to you — even if it’s to deny your request — within seven business days.

If their response takes longer, they have violated the Mississippi Public Records Act.

Once they respond, they may include a cost estimate.

If they don’t provide an itemized listing of charges, request it, especially if their estimate is steep.

If they can’t justify the cost by charging a flat fee, they have likely violated the law.

If that happens, you can file a public records complaint with the Mississippi Ethics Commission for free, and the Commission will investigate the matter for you.

An uninformed public, White said, is very dangerous, because they can enable these public officials to keep stealing.

“There was a school principal in Hollandale who we investigated. The state auditor’s office investigated and found that he embezzled over a hundred thousand dollars worth of money and property that belonged to the school,” White said. “He pleaded guilty to that. He was not adjudicated, which effectively in non-legal language means it it’s very hard to find on his record that he pleaded guilty to that thing. He then immediately moved across the state to Noxubee County. He ran for Superintendent of Education and he got elected over there.”

White said he worked with legislators last year to make it illegal to non-adjudicate those kinds of cases, making it easier to find those who violate the law.

“People need to understand when you allow somebody to stay in office, or heaven forbid, if you promote them to some higher office, you are going to put yourself at risk of losing more money,” White said.

3 On Your Side analyzed every one of the State Auditor’s demands for 2019 to see if these elected officials implicated for mishandling funds actually got re-elected after being investigated, and found two in Lincoln County.

Supervisors Nolan E. Williamson and William D. Falvey both won re-election in the November general election.

White’s office said both men, along with two other former supervisors, voted to improperly pay a county employee for bookkeeping services, and were ordered to pay the state more than $5,600.

That may not sound like a lot of money, but White says that kind of thinking is part of the problem.

“There are always people who are going to say, ‘Well that person stole about a thousand dollars. Why’d you throw them in jail?’ If you walked into the gas station on High Street and you stuck them up for $1,000, we’d throw you in jail. We’d put your picture on WLBT. We would publicize the fact that this happened,” White said. “So why is it any different if that person who walks away with a thousand dollars is a mayor who wears a tie? Why should it be any different?”

White said he’s even had to remind seasoned prosecutors that embezzlement and misappropriation of taxpayer money are not victimless crimes.

“They stole that money. They stole it from you directly. They looked you in the eye every single day when you walked in that office. When you saw them at church. And they knew they were taking money that belonged to you, and I’m the guy that comes along after the fact and holds them accountable,” White said.